The Poles: Human Impact

Harvesting from the land

There are no terrestrial mammals in the Antarctic, but the Arctic has plenty of mammals, including musk ox, reindeer, caribou, fox, hare, wolf, lemming, bears, and more.

The Inuit of the historical era have largely been dependent on mammals for warm clothing; the bearskin winter trousers of the Greenland hunter have been as distinctive as the guardsman's busby. Caribou killed in August, when the new hair is still short and fine, provided the most popular clothing skins. Musk ox robes and skins of caribou killed in winter were used for bedding.

With social and industrial development, conservation of Arctic fauna has demanded increased attention. Recent developments include restrictions by the US on the import of sea mammal products; imposition by the International Whaling Commission of quotas on the take of bowheads by Alaskan native hunters; signing of an international convention on the conservation of the polar bear (particularly on the high seas) by the US, Norway, Denmark, the former USSR and Canada; and the devolution of game management authority to Canadian Inuit organizations after land claim settlements.

Other threats to Arctic animals may include the impact of pollution (industrial and military) from the south on more fragile ecosystems, and more harvesting pressure as human populations grow.

Harvesting from the sea

When early Arctic and Antarctic explorers returned home and described the abundance of seals and whales they had seen, sealers and whalers were drawn to these new waters to hunt the valuable animals. Hunting was so intense that some species were driven nearly to extinction, and sealing and whaling slowed down only when there were too few left to make the hunts profitable. Agreements among nations now protect most seals and whales limiting how many can be killed.

Populations of most Antarctic seal species have increased dramatically. Most whale species, though, still number fewer than they once did, and some nations continue whaling in polar waters. Today, the bowhead whale is the only truly endangered Arctic mammal.

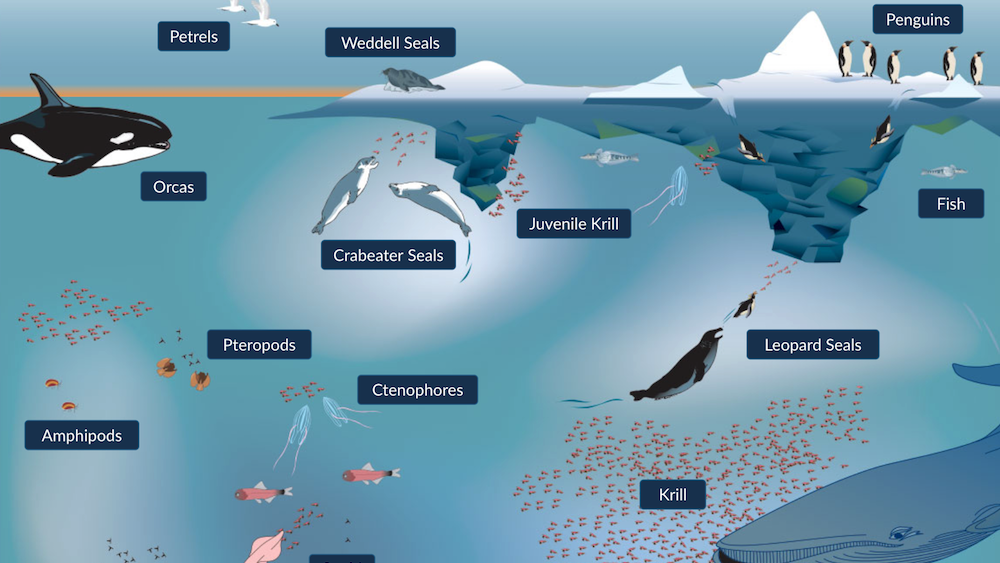

Antarctic Ecosystem: Human Impact

When early Antarctic explorers returned home and described the abundance of seals and whales they had seen, sealers and whalers were drawn to Antarctic waters to hunt the valuable animals. Hunting was so intense that some species were driven nearly to extinction, and sealing and whaling slowed down only when there were too few left to make the hunts profitable. Agreements among nations now protect most seals and whales limiting how many can be killed. Human settlements in Antarctica have often left traces of their presence behind; some are now preserved historic sites.

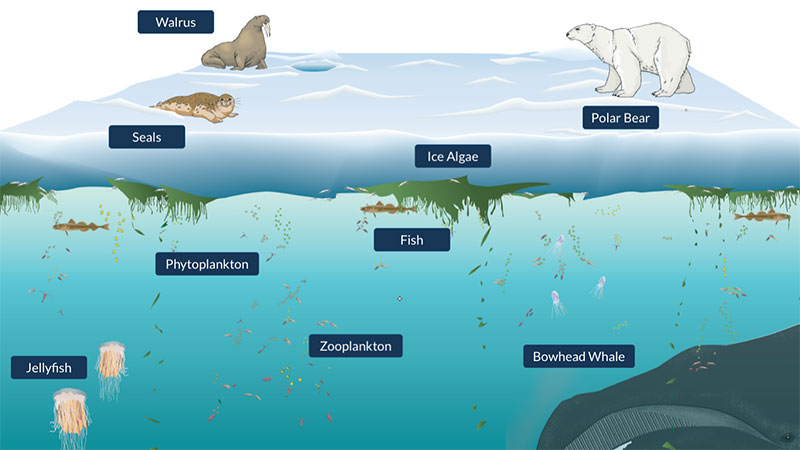

Populations of most Antarctic seal species have increased dramatically. Most whale species, though, still number fewer than they once did, and some nations continue whaling in Antarctic waters. Today, fish and krill are the only large-scale animal fisheries in the Southern Ocean, but many sea birds, especially albatrosses, are killed by fishing lines. Factory ships made huge catches possible, and some scientists are concerned that so many krill will be taken that it may affect the food supply for Antarctica’s predators.

Global Warming: Is the Ice Melting?

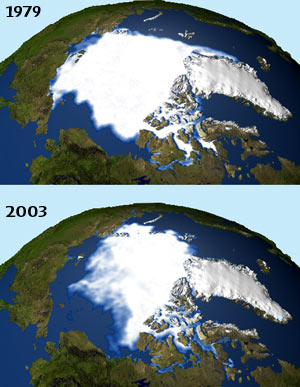

In 2005, the ice cap covering the Arctic Ocean shrank to its smallest size since researchers began keeping records a century ago. In the past five years, scientists reported that many Greenland glaciers are sliding faster to the sea and melting at their edges.

Melting sea ice has consequences. If the sea ice disappears, heat from the sun—which mostly reflects off white ice surfaces and back into space—instead would be absorbed by the ocean. This would further accelerate the warming of the Arctic resulting in more warming. Melting glaciers on land would raise sea level.

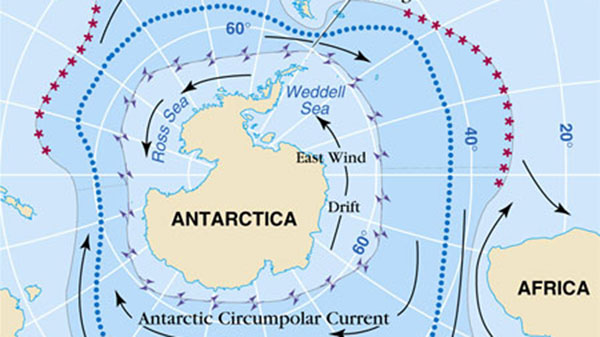

Melting sea ice also means more fresh water in the ocean, which could flood into the North Atlantic. That could disrupt a global system of currents, known as the Ocean Conveyor. The Conveyor brings warm, salty Gulf Stream waters northward, where they release heat to the atmosphere in winter and temper the North Atlantic region’s climate. The waters then become cold enough again to sink to the abyss, propelling the underside of the Conveyor. If more cold, fresh water is added to the North Atlantic it could put a lid of lighter water over the warm water and block it from releasing its heat to the atmosphere and sinking to drive the Conveyor. This could significantly cool the climates of Europe and North America.

Let's see how the ocean circulates in the North Atlantic.