Day 8: Weird & wonderful creatures of the MOCNESS

By Michelle Cusolito

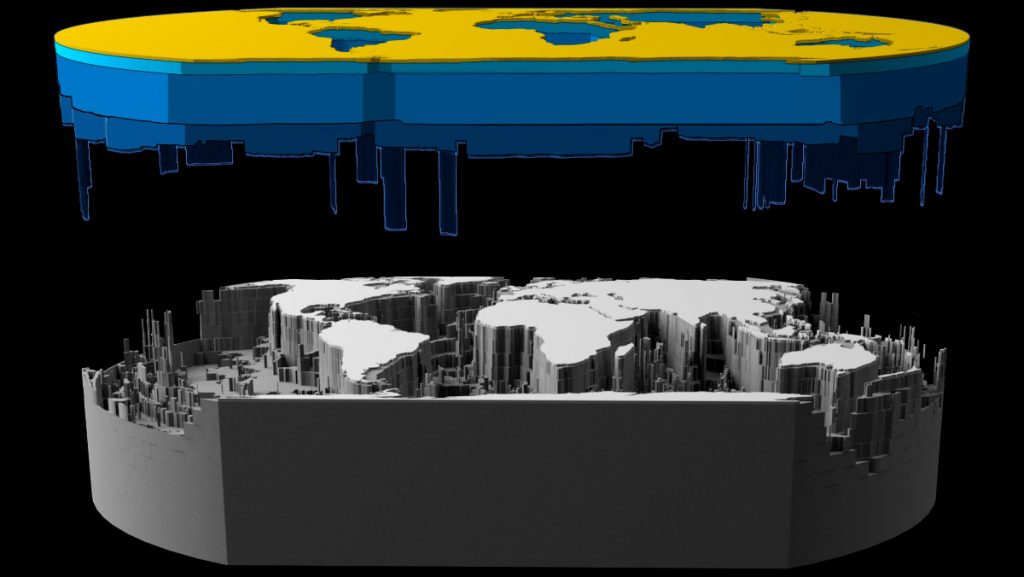

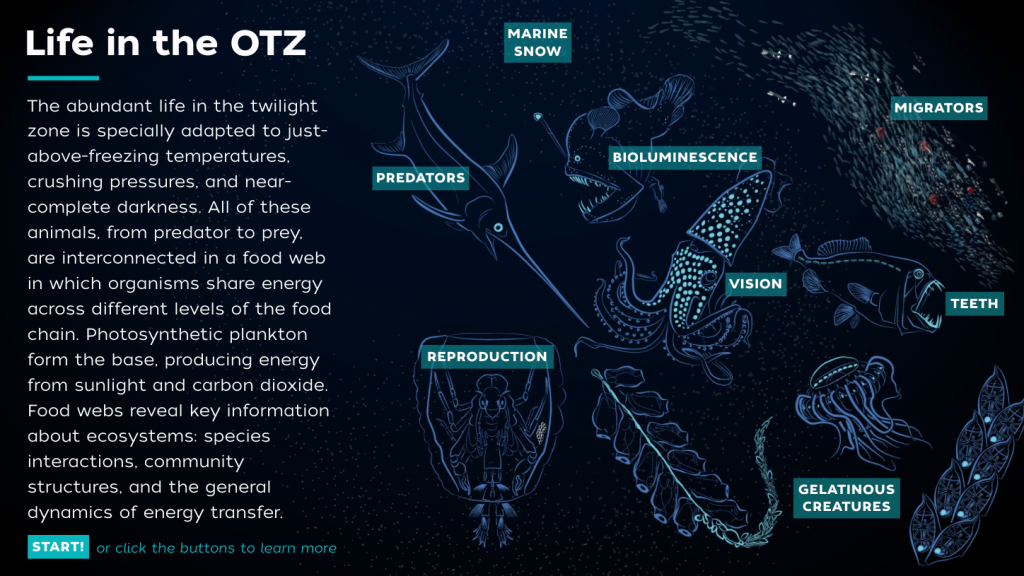

Members of the science team and the ship’s crew huddle around buckets and trays in the wet lab. They’ve gathered to admire the animals brought back from the deep by the MOCNESS (Multiple Opening/Closing Net and Environmental Sensing System). Most people never get to see deep-sea creatures in person. We all know it is a rare gift, brought to us by MOCNESS. Because scientists can trigger the nets to open and close at specific depths, this system is particularly useful for learning about animals of the ocean twilight zone.

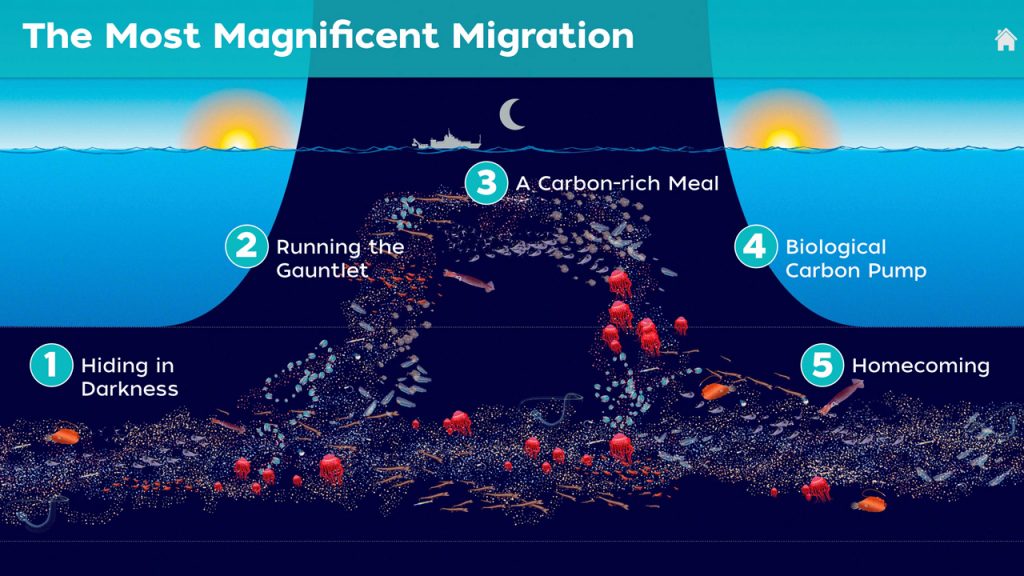

“The greatest strength is that it samples from different depths so we can know where the critters came from,” says Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI) biologist Joel Llopiz. “We want to study the active movement of carbon—due to swimming—so with these nets we can know who migrates up and down on a daily basis and who doesn’t.”

While smaller MOCNESS systems are fairly common on research vessels, the one being used on Sarmiento de Gamboa is unusual. This monster has a 10 square meter (108 square-foot) opening!

As I admire a tray full of animals including Atolla jellies, shrimp, and pteropods with Laetitia Drago (Institut de la Mer de Villefranche), she turns to me with a giant smile that rises all the way up to her eyes. “This is what dreams are made of!”

While the rest of us marvel at the different organisms, the net team has already swung into action. Helena McMonagle (University of Washington) takes the live fish to a darkened lab downstairs where she measures their respiration rates. One way fish can release carbon is by breathing. Helena hopes this experiment will help her understand how much carbon is carried to the deep ocean by fish and then released by their breathing.

As Joel says, “the deeper the fish go, the deeper the carbon gets.”

Photographer David Liittschwager takes two glass squid, several shrimp, and an ostracod down to a different lab to shoot detailed, close-up photos. He cleans the clear dish he’ll use to hold the delicate specimens and fills it with seawater that’s constantly flowing into a sink. He gently transfers the delicate creatures, then moves to his camera to begin shooting photos.

Meanwhile, Kayla Gardner (MIT-WHOI joint program) and WHOI research assistant Julia Cox guide Cristina Garcia Fernandez (Institute of Marine Research) through the collection protocols. First, Julia and Cristina remove any fish they find, label them with depth and location information, and immediately freeze them in liquid nitrogen for future study.

Kayla strains the remaining live samples through a sieve. Then she passes the plankton that remain in the water to Julia and Cristina who use a splitter to separate the sampling into four equal parts. One part is frozen, one part is preserved in formalin, and the final two parts are preserved in ethanol. Splitting the samples in this way allows scientists with different areas of expertise to study the organisms as comprehensively as possible once they get back to their labs at WHOI.

After this first net tow, we’re all excited to see what the MOCNESS will bring up in the next two weeks.