Day 11: Three ships are better than one

By Marley Parker

Imagine you’re planning an oceanographic expedition. You need to pinpoint the right place in the ocean at the ideal time of year and secure funding for an appropriate vessel. Then you need to ship equipment and supplies and coordinate dozens of schedules — just to bring a team of scientists and engineers together on one ship.

Now multiply that effort by three, add in the critical safety measures and precautions of traveling and working in close quarters during the COVID-19 pandemic, and you’ve got this expedition: three ships carrying a total of 150 scientists and crew members. By every measure, it is a remarkable feat.

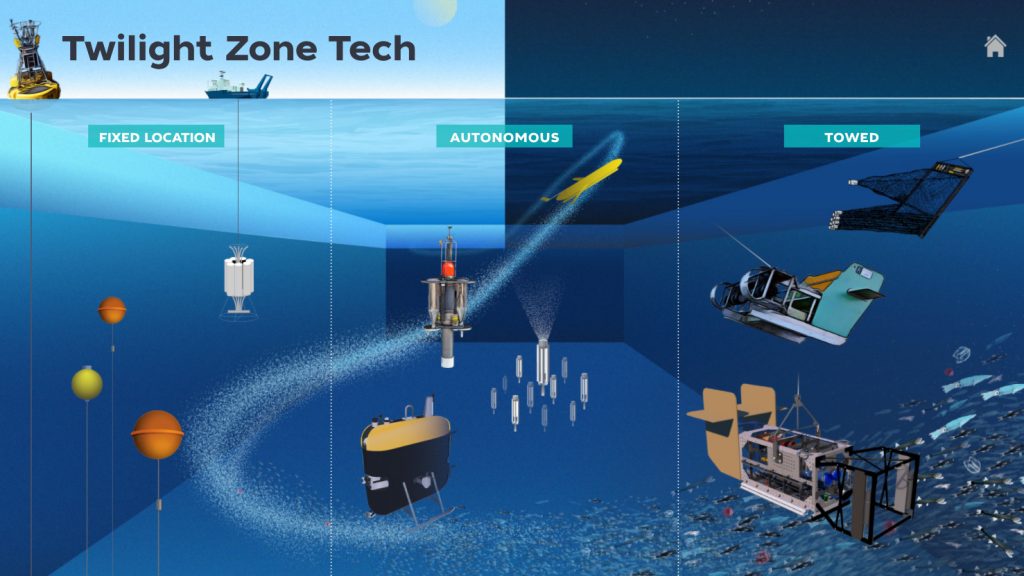

It’s a feat that has been years in the making and has involved collaboration between multiple organizations including Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution’s Ocean Twilight Zone project, the National Science Foundation, and NASA Earth Science. Through this partnership, we have instruments collecting data in the ocean, on the ocean, from shore, and in outer space.

“What we’re doing is unprecedented in terms of number of people, amount of effort, and the types of measurements we’re taking,” says co-lead scientist Ken Buesseler.

So why do we have three ships in this part of the North Atlantic at the same time?

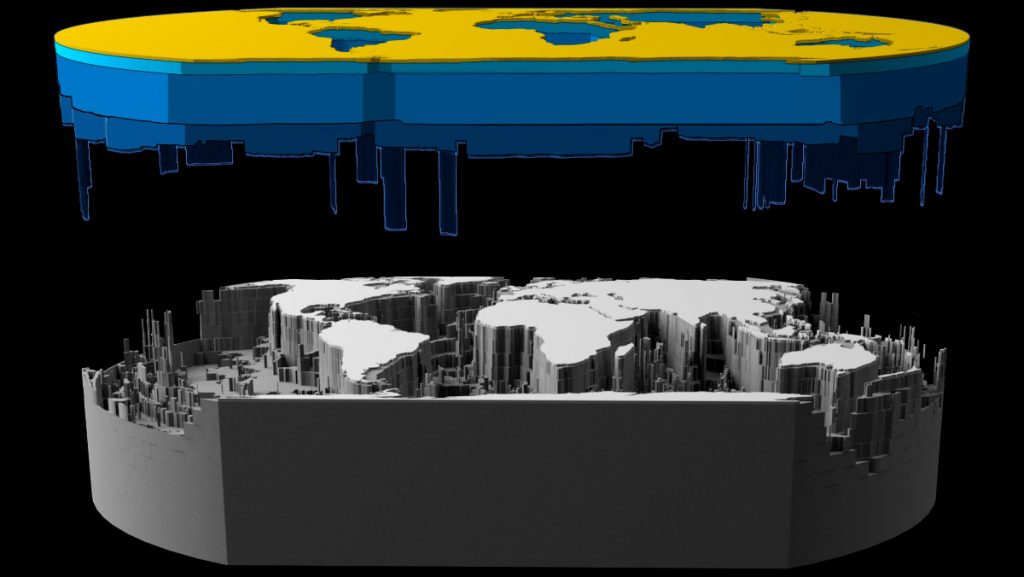

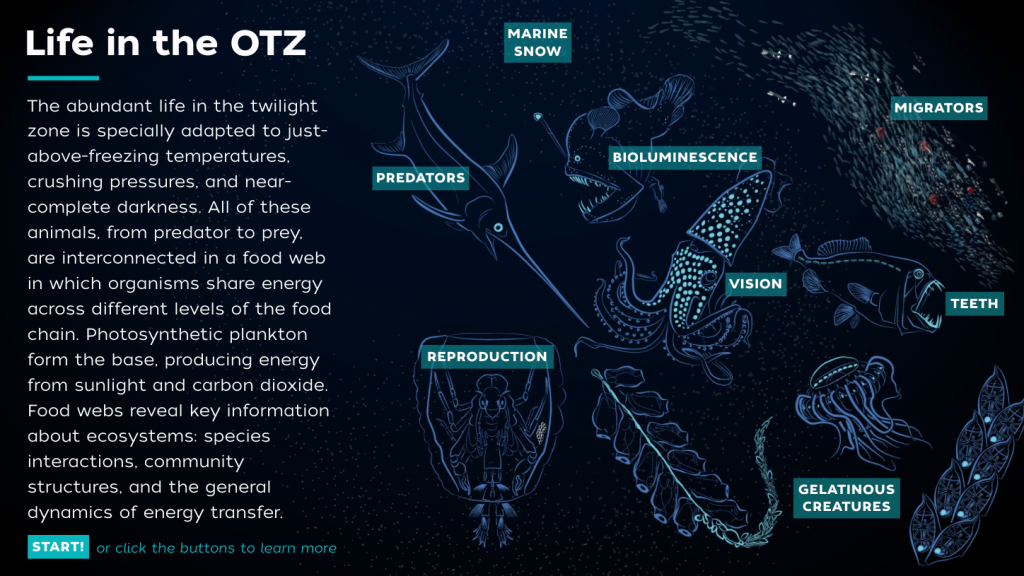

Because it’s the only way to get a truly comprehensive view of what’s going on in the mid-ocean “twilight zone” during the spring phytoplankton bloom.

“Obtaining all of these measurements simultaneously is key,” Ken says. “That’s never been done.”

While all three vessels are coordinating various science operations, each has its own special focus.

The RRS (Royal Research Ship) Discovery provides detailed mapping of the study site. The RRS James Cook examines biological processes in the center of field operations. The Sarmiento de Gamboa focuses on deploying new technology and collecting biological samples from higher up the food chain.

On two occasions, the captains have brought all three ships within a couple hundred meters of each other.

“Moving three vessels at the same time is a complex maneuver—it’s not like we’re at the dock,” says Miguel Ángel Menéndez Pardiñas, captain of the Sarmiento de Gamboa. “But the dynamic positioning system allows us to stay in one place. We try to make things easy and safe for everyone.”

Moving the ships close together for short intervals has gone smoothly, in part due to excellent communications between all the captains and chief scientists.

The novelty of three research vessels operating in close proximity continues to delight everyone on board. Each time we look up and see one or both ships on the horizon, we feel a sense of comradery. We take a break from work to wave, snap photos, and exchange messages with our colleagues on the other vessels.

“In reality, we’re just a ship next to another ship,” says WHOI senior research assistant Justin Ossolinski. “But even for oceanographers who have been going to sea for years, this is totally unique.”