Day 12: Small but mighty MINIONs

By Marley Parker

On a bright, breezy morning, six of us stand on the aft deck holding Pyrex tubes full of 3D-printed materials, wires, and circuit boards. As the wind whips our faces, Jackson Sugar works with Bosun Oscar Orizales Breijo to attach each instrument to a rope, which they carefully lower over the side of the ship.

After watching all four instruments sink below the surface, Oscar slaps Jackson on the back and says, “I like your method because it’s very simple!”

That’s the idea.

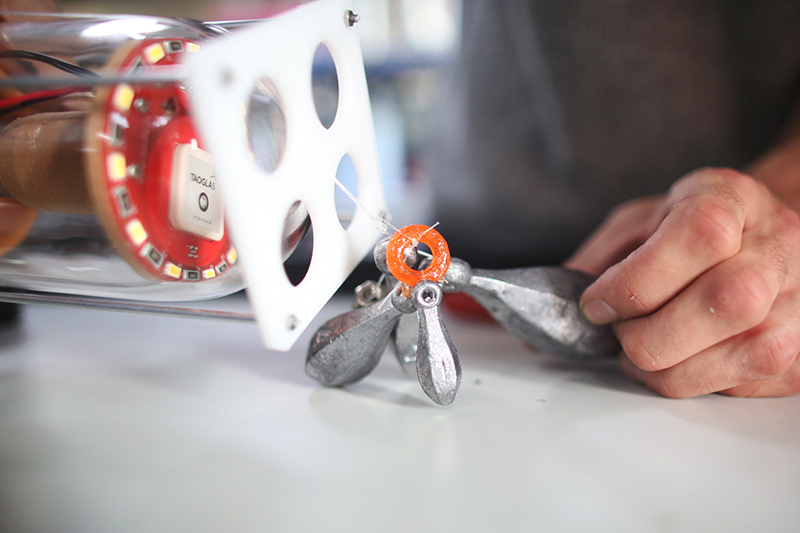

For the past four years, Jackson has been working in Dr. Melissa Omand's lab at the URI Graduate School of Oceanography, refining the design and functionality of these nifty devices, called MINIONs" working on refining the design and functionality of these nifty devices, called MINIONs. Each one contains a camera, lighting device, a Raspberry Pi computer, and a custom, low-power circuit board. Though small and inexpensive, these instruments can tell us a lot about what’s happening several hundred feet below the surface of the ocean.

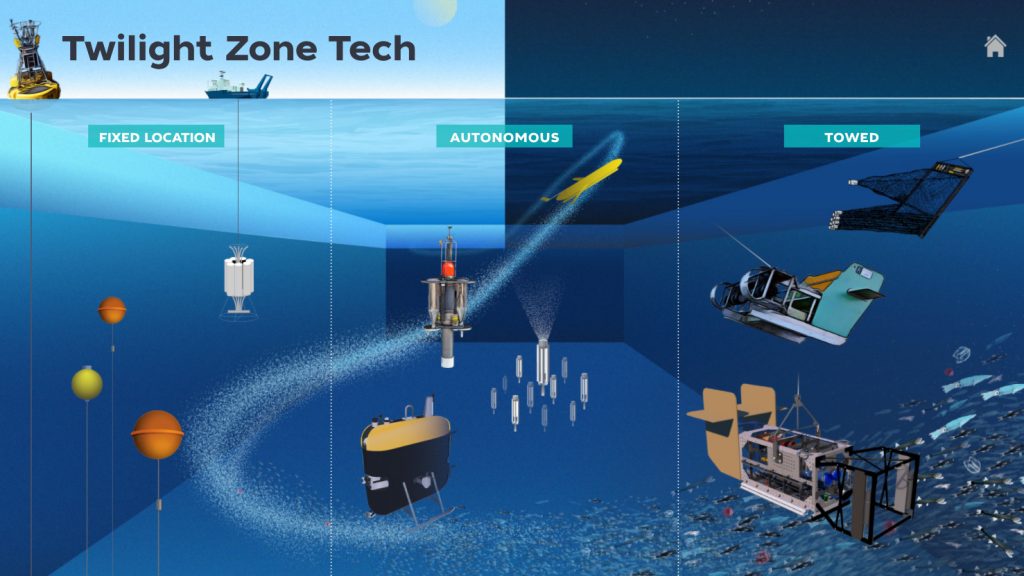

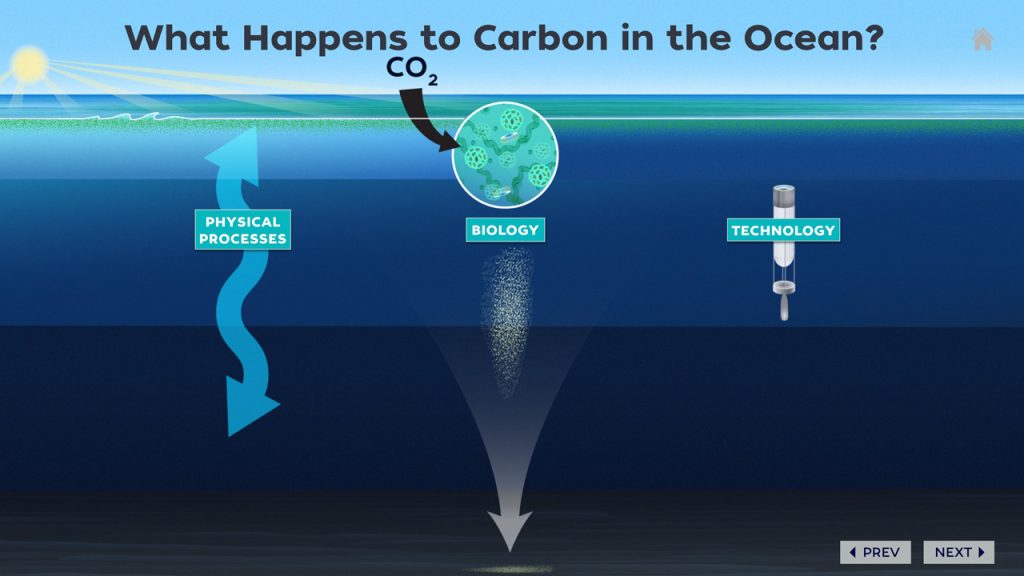

Once in the water, the MINION captures a time lapse of photos. These images of marine snow and other particles provide valuable insight into how carbon moves throughout the ocean twilight zone. After the MINIONs pop up again at the surface, Jackson will retrieve them and wirelessly copy all the images on their tiny computers, as well as the pressure, temperature, and accelerometer data they collected.

But we’re in the middle of the ocean, in less-than-ideal conditions, so we’re just crossing our fingers that we get the MINIONs back.

“This isn’t the first time I’ve deployed MINIONs, but this is definitely the most challenging location in terms of sea state,” Jackson says, gazing out at the rolling waves. “I’m cautiously optimistic.”

While we’re only deploying four MINIONs today, the long-term goal is to position hundreds of them in a particular area, where they can collect data across various locations and depths at the same time. In the future, all these MINIONs will stay in the ocean for weeks at a time, sending data back to shore via satellite.

“It’s still a prototype – we’re working out the kinks,” Jackson says. “This is the third iteration.”

About nine hours after the deployment, we receive a message from co-lead scientist Ken Buesseler. “Anyone with binoculars or just good eyes is welcome on the bridge to help spot MINIONs.”

Several members of the science team finish eating dinner quickly and race up to the bridge. As we stare through the windows in the fading evening light, Jackson explains that the MINIONs flash three times at a random interval every four seconds so that the rhythm of the flashing light doesn’t sync with the wave period.

After 20 minutes of squinting at the horizon, Justin Ossolinski spots the telltale flashing strobe. Jackson rushes downstairs with the technicians to go fishing for it. Because we’re still in relatively rough conditions, recovery is challenging. But just over an hour later, Jackson walks into the lab, holding up the MINION victoriously.

“Doing low-cost science comes with a particular set of compromises,” Jackson says. “But successfully completing a mission and proving that this technology works is exciting for the future of oceanography.”