|

|

Interviews: NOAA’s

Craig McLean Question:

When did the scuba diving urge first strike you? Craig: What probably did me in was watching the TV show “Diver Dan.” My mom got me and my brother plastic astronaut hats, and I combined mine with a set of plastic Scuba tanks. I crawled around the living room floor, using pillows for boulders, trying to emulate the work of an undersea diver. When I got to be 14, my father told me he would give me permission to take diving lessons, but I had to find a job and pay for them on my own. Right next to my house was a boatyard, and the next day, the boatyard owner bangs on our door and says to my mom, “Which one of your two boys would like to come and work in the boatyard?” My father swears to this day that he had nothing to do with that. Question: So you didn’t have to find a job. It found you. Craig: Yep. I wound up working in that boatyard, chipping barnacles and moving boats with house jacks. It gave me a good appreciation of what the maritime was all about. And it also gave me the capital to take diving lessons and buy gear, and I started diving on shipwrecks in New Jersey coastal waters. On weekends, I worked on dive boats. Once we had a group that wanted to film the dumping of sewage at an offshore dump site. I wound up swimming a camera under a sewage barge as it dumped its load on top of me. I got some great footage, and then got out of there as quickly as possible. Question: What did you study in college? Craig: Zoology. Once, I was invited by a professor to sail on a NOAA ship, the Kelez, as part of investigation of how sludge dumping might affect microbes in the ocean and cause public health problems. It gave me a good look at the art and practice of marine science. Question: And after college? Craig: I was diver for a diving company for two years. But then I came to Woods Hole to work on a NOAA ship. I had been a small-boat guy, but when I saw what ship operations were like, I enjoyed it and wanted to do more. I went to Kings Point for an abbreviated nautical training course, and I joined the NOAA Commission Corps. It is the seventh uniformed service in the US—like the Navy and Air Force. Give someone a prize if he can name all seven. Besides NOAA, the one people usually overlook is the Public Health Service. Question: Give us a brief tour of your early career in NOAA. Craig: My first assignment was as a deck officer and diving officer on a hydrographic survey ship, mapping nautical charts. Then I worked shoreside in the National Marine Fisheries Service, working on strategies to harvest fish stocks at sustainable levels. I spent a lot of time on ships studying fisheries. I was executive officer on the Albatross and captain of the 225-foot NOAA ship Gordon Gunter. Question: Then you went back mid-career to law school. Why? Craig: I had a fair bit of practical experience, from sanding hulls and diving to sailing vessels. I wanted to add in a different set of tools so that I could effect changes in regulations and laws. I prosecuted violations of the Marine Mammal Protection Act and the Endangered Species Act. I reviewed proposed legislation that affected NOAA. I was the lawyer, and later Deputy, for the National Marine Sanctuary System, which is a series of 13 marine sites, from American Samoa to Stellwagen Bank off Cape Cod. These sanctuaries are protected by law and designated to be preserved from further development.

Now you are Director of NOAA’s new Ocean Exploration Program. Tell us about it. Craig: Our country has had a long-term national strategy to explore space, but we have not had a similar approach to explore the oceans. The Ocean Exploration Program was started just last year in response to a panel of national experts who recommended that we refocus our attention on the oceans. We use the oceans, but we don’t fully understand them. When we talk to ocean scientists, they say, “Gosh, I got into science to explore and discover, but without sufficient funds to do that, it’s frustrating, and it slows our progress.” Our goal is to change the way America thinks about the oceans and to give ocean exploration a long-needed push. We’re willing to take a few risks—to try experimental technologies and take on more difficult expeditions—to accelerate advancement of our knowledge of the oceans. Question: Despite all your varied travels, you had never been down in Alvin before this cruise. What was that like to dive to a hydrothermal vent site? Craig: What an amazingly complex oasis in the middle of a desert! The diversity and abundance of creatures was surprising to me. But the interactions between animals were all in slow motion. When I graduated college with a degree in zoology in 1979, what I had learned was already out of date—because the hydrothermal vents had just been discovered. Diving in Alvin reinforced my appreciation that we have to increase our funding for ocean exploration, and we have to let the public know what ocean science is teaching us. |

||||||

Mailing List | Feedback | Glossary | For Teachers | About Us | Contact

© 2010 Dive and Discover™. Dive and Discover™ is a registered trademark of

Woods

Hole Oceanographic Institution

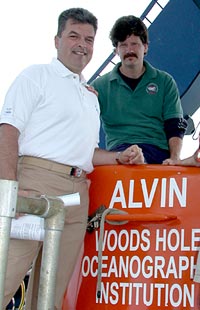

Before

his first dive in Alvin, McLean gets a lesson from Kang Ding

on how to use Kang’s special temperature and chemical sensor,

which is attached to Alvin’s manipulator arm.

Before

his first dive in Alvin, McLean gets a lesson from Kang Ding

on how to use Kang’s special temperature and chemical sensor,

which is attached to Alvin’s manipulator arm.