Galápagos Rift

Hydrothermal Vents

Expedition 6:

May 24-June 4, 2002

Mission & Objectives

Daily Updates

Mail Buoy

Scientists & Crew

Interviews

Hot Topics

Slideshows

Videos

Glossary

|

Interviews: Principal Engineer Al Bradley

Interview by Lonny Lippsett and Sharon Franks

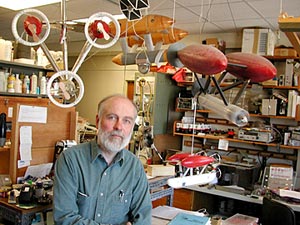

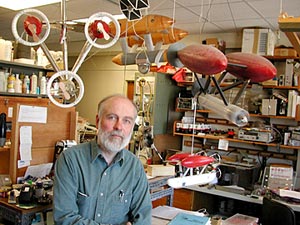

Al

Bradley in his office surrounded by models of some of the “toys” he invents to help scientists solve problems. Al

Bradley in his office surrounded by models of some of the “toys” he invents to help scientists solve problems.

Question: A toy maker?

Al: I have a hypothesis that playing with toys is a fundamental

evolutionary instinct. It teaches you what you’re good at,

what your brain will be successful at. So I played with Tinker Toys

and Erector Sets and radio kits. I was a compulsive gadget-builder.

I knew that I had to study engineering.

|

|

| At

11 years old, Al Bradley and a friend tried to make a submarine

out of wood. Here, Al tries it out for size. |

Question: So why didn’t you end up building bridges or cars, for example?

Al: At age 10, I saw two absolutely pivotal movies—Jacques

Cousteau’s first color movie, “The Silent World,”

and Walt Disney’s “20,000 Leagues Under the Sea”—and

I just totally fell in love with the idea of going under water.

I spent my youth trying to build submarines.

Question: Did you build any?

Al: At age 11 I tried to make a submarine out of wood.

My father was very wise. He said, “If you can keep the water

out of this for 15 minutes, I’ll let you get in it and try

it.” My dad knew I couldn’t succeed at age 11 to make

a waterproof hull. The submarine was ridiculous. It was L-shaped,

so you could sit up in it. But we had a lot of fun.

Question: Did you actually test it?

Al: Well, I put it in the water and watched the water

flow in through the quarter-inch gaps where the boards met. The

experience taught me how to saw a straight line.

Question: And you tried again?

Al: Oh yes. In college I had a project to make a two-man

wet sub. How to make the propulsion system was beyond me at the

time, however. So the sub had wooden flippers that looked like frog

legs. It ended up as a playground toy in a pre-school.

Question: And after college?

Al: Then I discovered that engineers could work with

ocean instruments. I got a summer job at Woods Hole Oceanographic

Institution. I found out that the world’s top oceanographers

chose to spend their coffee breaks in the galleys of the ships,

shooting the breeze with the stewards, the able-bodied seamen, the

captains, and the chief engineers. The scientists knew they had

a lot to learn from the ships’ crews. And the ships’ crews

were not just bus drivers. They wanted to talk science with the

scientists. That was the mind-set of Woods Hole.

|

|

| Al

Bradley works at the bench in his lab testing the computer “brains” of the autonomous underwater vehicle, ABE. |

Question:

Does it work in a similar way with the scientists and engineers

at WHOI?

Al: It’s very much a two-way street. The scientists

are driven by curiosity about the universe, about how things work.

The engineers are driven to make things. The scientists want to

find out something, and I bring the world of engineering to bear

on how to build something to get them what they need. The magic

happens where the two worlds meet. The solution usually comes after

many discussions and a long period of gestation.

Question: Did that happen when you developed ABE,

the Autonomous Benthic Explorer?

Al: Oh yes. That’s an interesting story (See Part

II of Al’s interview tomorrow.)

Question: On this cruise, ABE will be diving in the late

afternoon for 6 to 8 hours and then returning in the early morning.

But you have used ABE for longer stretches, right?

Al: We’ve gotten past the milestone of putting ABE

down, leaving it there, going off out of contact, to do an Alvin

dive in another location, and then coming back to retrieve ABE.

Of course, we’re always nervous when we do that.

Question: Because you don’t like to lose your toys—especially

when they are so expensive?

Al: That’s what I do. I’m one of the very fortunate

people who can continue to play with toys. And, I believe, they

are quite useful.

Question: How was ABE born?

Al: Originally, Barrie Walden (head of the Alvin Group at WHOI) came to us and said, “Half the scientists’ requests for Alvin dives are to return to look at places where we’ve already been. Could we build something that descends to the ocean bottom with a weight, finds a sound beacon on the seafloor, takes a picture, drops its weight, and pops up again? Then we could save Alvin for missions that only it could do.” We said, “OK, sure, but let’s think about that. What if this device could hold its position near the seafloor? And what if we give it some minimal thrusters so that it can move horizontally along the bottom? That’s much better, because you could get a series of pictures along a line, not just one picture.”

That seemed good, but then we said, “OK, let’s think some more. If this vehicle can home into a sound beacon, why not have it go out on a line, and then come back and find the beacon again—and then go out on another line, like the spokes of wheel, so that you can survey a 50-meter circle at one time? This was an incredible step beyond the first concept of diving down to get one picture, and it wasn’t that much more complicated.

|

|

| Al Bradley and Dana Yoerger, co-inventors with Barrie Walden of ABE, work together to design underwater vehicles for scientific research. |

Question: But apparently you kept on thinking.

Al: Yes, we said, “Wait a minute. If we have something that can home into a beacon and maneuver near the seafloor, why don’t we just add a latching mechanism, so that it can come back and anchor to the beacon? Then it can shut down, go to sleep, wake up again in an hour, or two days, or a week, and go out and do it all over again. Suddenly we opened up a whole new dimension of possibilities for scientists.

Question: Please explain.

Al: Whenever you put a camera in an interesting place on the seafloor, it gets crudded up with bacteria. And if you put it out in cold water where it won’t get crudded up, you don’t see anything interesting. Our new “thing” could go to sleep in cold water, come in to the target site, take a series of photographs, go back out, and sleep in cold water. The goal was to give geologists and biologists a series of photos over time—photos of a field of tubeworms growing, for instance, or a field of black-smoker chimneys growing and decaying. That was the original concept for ABE, and we had never built a device like that before.

Question: But then ABE evolved some more?

Al: We had tested ABE in Woods Hole harbor, but we had to try it out in the deep ocean. So we looked for an opportunity to test it. (WHOI geophysicist) Maurice Tivey took a risk. He was going on cruise to the Juan de Fuca Ridge, and he said. “Why don’t you come along and try putting my instruments on ABE. Maybe you can use it to get magnetics data for me.” But just in case, he also towed a magnetometer and used all the regular devices—just to make sure he got the information he needed.

Question: How did it go?

Al: Maurice was ecstatic. ABE collected data on the magnetic properties of seafloor rocks that were far superior than what you can get with Alvin. Alvin can collect magnetics data perfectly well. But it’s ill-suited to that task. To get magnetics data, you need to fly in a perfectly straight line and slightly out of visible contact with the bottom. Alvin pilots prefer not to do that. Alvin is better suited to bring people to the bottom and look at something closely, or to pick up something. It’s a waste of Alvin’s time to just go back and forth, out of visible range of the seafloor. But ABE could do that. It became clear that ABE was a superb surveying tool. So we switched our thinking and said, “Don’t just put ABE down and dock it. Get that thing right back up to surface after a dive, get out the data, recharge its batteries, and send it back down as fast as you can.” That way we could get much more data and cover much more ground.

|

|

| ABE, the Autonomous Benthic Explorer, is recovered after a mission to the seafloor. |

Question: And you’ve added other instruments onto ABE so that it can acquire more kinds of information.

Al: We’ve added a scanning sonar, so that instead of sending just one “ping” of sound that bounces off the seafloor, ABE puts down a fan of 25 pings. That allows us to get an image of the seafloor with much more texture. After this cruise, in the 10 days before we leave on our next cruise, we hope to install a multi-beam sonar that sends out 64 or 128 “pings,” instead of 25 beams. And there are lots of other instruments we want to put on ABE.

Question: What happened to the original plan of docking ABE on the seafloor for long periods of time?

Al: There’s no reason not to go back to the original scenario eventually. We just found that ABE was useful in other ways that we hadn’t originally anticipated.

|

Al

Bradley in his office surrounded by models of some of the “toys” he invents to help scientists solve problems.

Al

Bradley in his office surrounded by models of some of the “toys” he invents to help scientists solve problems.