|

|

|

The Deep-Tow geophysical instrument package of Scripps’ Marine Physical Laboratory is equipped with precision sonar, cameras, and geophysical sensors that transmit data back to the ship via a cable. (Photo courtesy of Scripps Institution of Oceanography) |

|

|

|

|

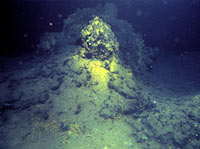

The Southtow expedition found intriguing mineral-encrusted mounds sticking out of seafloor sediments. The mounds, like this one photographed on the 1977 Galápagos expedition, are formed by hydrothermal venting. (Photo by David L. Williams, USGS) |

Deep-Tow finds seafloor mounds

Scripps scientists and engineers led by Fred Spiess had built a deep-sea sonar and camera system called Deep-Tow. They were largely funded by the U.S. Navy, which wanted to develop equipment that could be rushed to sea to conduct searches on the seafloor. The Navy was motivated by the tragic loss in 1963 of the nuclear submarine Thresher, which sank along with its 127-member crew in 2,500 meters (8,250 feet) of water and could not be found quickly.

Deep-Tow also proved to be a very useful tool for scientific investigations. It was one of the first deep-submergence vehicles used by civilian scientists, and it collected data that led to many important discoveries. Deep-Tow is a big metal “fish” that is towed near the seafloor by a long cable attached to a surface ship. The “fish” is packed with instruments, including underwater cameras, magnetometers, and sonars. The cable transmits data back to scientists on board the ship.

On the Southtow expedition, Deep-Tow’s camera found curious, roughly circular mounds sticking out of seafloor sediments about 18 to 36 kilometers (10 to 20 miles) south of the Galápagos Rift’s volcanic valley, near latitude 86°W. The mounds were 4.5 to 23 meters (15 to 75 feet) high and 18 to 45 meters (60 to 150 feet) in diameter. Many were crusted with minerals. Their shape and composition indicated that they were deposits formed by hot, mineral-rich fluids circulating in top layers of the ocean crust.

| Page

4 |