|

Scientists

prepare to lower a heat-flow probe to the seafloor from the fantail

of R/V Thomas Washington in 1972. The probe allows scientists

to calculate heat flowing through seafloor sediments. (Courtesy

of Scripps Institution of Oceanography) |

|

The

Southtow Expedition, on board Scripps Institution of Oceanography's

R/V Thomas Washington in 1972, found clues leading to the discovery

of hydrothermal vents at the Galápagos Rift. (Courtesy

of Scripps Institution of Oceanography) |

|

The

Deep-Tow geophysical instrument package of Scripps’ Marine Physical

Laboratory is equipped with precision sonar, cameras, and geophysical

sensors that transmit data back to the ship via a cable. (Courtesy

of Scripps Institution of Oceanography) |

|

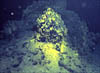

The

Southtow expedition found intriguing mineral-encrusted mounds

sticking out of seafloor sediments. The mounds, like this one photographed

on the 1977 Galápagos expedition, are formed by hydrothermal

venting. (Photo by David L. Williams, USGS) |

|

Mike Legg, then a graduate student on theSouthtow expedition, throws

a sonobuoy overboard to detect micro-earthquakes at the seafloor.

(Courtesy of Ken Macdonald, UCSB) |

|

Scientists

on Southtow analyzed dead bottom-dwelling fish that they found

floating on the sea surface. The fish were found in an area where

scientists had detected a swarm of seafloor micro-earthquakes. (Photo

by Philip Hastings, Scripps Institution of Oceanography.) |

|

K.O.

Emery of the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution received a letter

from French scientist Xavier Le Pichon proposing a joint U.S.-French

expedition to explore the Mid-Atlantic Ridge. (Courtesy of WHOI Archives) |

|

The

200-ton French bathyscaphe Archimède was one of three submersibles

that participated in Project FAMOUS. (Courtesy of WHOI Archives) |

|

The

French submersible Cyana took part in Project FAMOUS. (ourtesy of IFREMER) |

|

Alvin is photographed from Cyana’s viewport on

the Mid-Atlantic Ridge during Project FAMOUS. (Courtesy of WHOI

Archives) |

|

Alvin is refitted with its new titanium sphere to double its

diving range to 12,000 feet. (Courtesy of WHOI Archives) |

|

WHOI’s

James R. Heirtzler was the U.S. leader of Project FAMOUS. (Courtesy

of Scripps Institution of Oceanography) |

|

Project

FAMOUS used the U.S. Navy’s LIBEC camera system, which suspended

high-intensity electronic flash lamps well above the ocean bottom.

(Courtesy of U.S. Naval Research Laboratory) |

|

The

LIBEC system shot 120-foot-wide sections of the seafloor that were

pieced together. (Courtesy of U.S. Naval Research Laboratory) |

|

LIBEC

collected 5,250 seafloor photos, which were fitted together and laid

across the floor of a Navy gymnasium in Washington, D.C. (Photo by

Emory Kristof © National Geographic Society) |

|

Alvin and its former mother ship, Woods Hole Oceanographic

Institution’s R/V Lulu. (Courtesy of WHOI Archives) |

|

The

Alvin group prepares to lift the sub to R/V Knorr’s fantail

for the trip to Project FAMOUS’s Mid-Atlantic Ridge dive sites.

(Photo by Frank Medeiros) |

|

Alvin pilot Jack Donnelly (middle) is flanked by two divers.

(Courtesy of WHOI archives) |

|

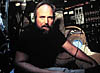

WHOI’s

Bob Ballard nervously monitors pilot Jack Donnelly’s efforts

to free Alvin, which became stuck in a seafloor fissure during

Project FAMOUS. (Photo by Emory Kristof, © National Geographic

Society.) |

|

The

Pleiades expedition on board Scripps’ R/V Melville

in 1976 added more clues to zero in on the Galápagos Rift vent

site. (Courtesy of Scripps Institution of Oceanography) |

|

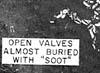

Deep-Tow’s

camera photographed telltale clamshells on the seafloor. (Photo

courtesy of Peter Lonsdale, Scripps Institution of Oceanography) |

|

The

clamshells were intriguing, but they were not proof of hydrothermal

vents. At first, some scientists thought the clamshells (especially

with a discarded beer can nearby) might be garbage thrown off a ship.

(Courtesy of Peter Lonsdale, Scripps Institution of Oceanography) |

|

Divers

prepare Alvin between the pontoons of its mother ship, Woods

Hole’s R/V Lulu. (Courtesy of WHOI Archives) |

|

ANGUS,

Woods Hole’s deep-towed camera system, is deployed during the

Galápagos Rift Expedition. (Courtesy of WHOI Archives) |

|

R/V Knorr, scientists and technicians stand vigil, tracking

ANGUS as it is towed near the seafloor in 1977. (Photo by Emory

Kristof © National Geographic Society) |

|

A

series of seafloor photos taken by ANGUS shows the sudden appearance

of a dense accumulation of live white clams. Within hours, the clams

led scientists to find hydrothermal vents for the first time. (Photo

courtesy of WHOI Archives) |

|

Alvin’s manipulator arm picks up a large clam from the

Clambake 1 vent site. (Photo by Robert D. Ballard, WHOI) |

|

ANGUS

captured this photo of a skate swimming above lava near the Galápagos

Rift vent site. (Courtesy of WHOI Archives) |

|

A

purple octopus scavenges in a clam-filled vent site (Photo by Robert

D. Ballard, WHOI) |

|

ANGUS

took this photo of dead clams at Clambake 2. The clams died because

the vent was no longer active. (Courtesy of WHOI Archives) |

|

Tubeworms,

white crabs, and a pink fish gather at a Galápagos Rift vent

site (Photo by John M. Edmond, MIT) |

|

Scientists

of the 1977 Galápagos Rift Expedition (left to right), Bob

Ballard, Jack Corliss, and John Edmond, convene on the deck of R/V

Knorr. (Photo by Ken Peal, WHOI.) |

|

Biologist

Fred Grassle dives to the Galápagos Rift vents in 1979 in

Alvin. (Photo by Al Giddings © National Geographic Society) |

|

WHOI’s

submersible Alvin was extensively modified to accommodate new

equipment for the biological dives to the vents. (Photo by Fred Grassle,

WHOI) |

|

Alvin

explores the Galápagos Rift vent sites in 1979. (Photo

by Emory Kristof © National Geographic Society.) |

|

The

curious creature first called a “dandelion” by geologists

during the 1977 cruise turned out to be a siphonophore, a cousin of

the Portuguese man-of-war (Photo by Al Giddings © National Geographic

Society.) |

|

Alvin’s

meter-long temperature probe extends toward a community of galatheid

crabs perched atop pillow lava and a dense field of mussels. (Photo

by Robert Hessler.) |

|

The

flesh inside the giant clams is blood red because it contained hemoglobin—the

same substance that transports oxygen inside human blood. (Photo by

Emory Kristof © National Geographic Society.) |

|

Biologists

on the 1979 Galápagos cruise use a respirometer to measure

the amount of oxygen mussels take up from seawater. (Photo by Ken

Smith, SIO) |

|

Spaghetti worms drape volcanic rocks on the seafloor near the vents. (Photo by James Childress, UCSB) |

|

WHOI

microbiologist Holger Jannasch searches for vent bacteria on a mussel

shell on the 1979 cruise. (Photo by Emory Kristof © National

Geographic Society.) |

|

‘Stands

of snow-white tubeworms crowned with feather-like blood-red plumes.’

(Photo by Emory Kristof © National Geographic Society.) |

|

The

first black-smoker chimney ever seen by humans—photographed at

21°N in 1979. (Photo by Dudley Foster, WHOI) |

|

The

chimney “smoke” really consists of superheated (350°C

or 662°F) fluids that are filled with dark mineral particles.

(Photo by Dudley Foster, WHOI) |

|

Black-smoker

chimneys form when superheated fluids hit near-freezing seawater.

Minerals in the fluids precipitate quickly to form tubes that can

grow very tall. (Photo by Patrick Hickey, WHOI) |